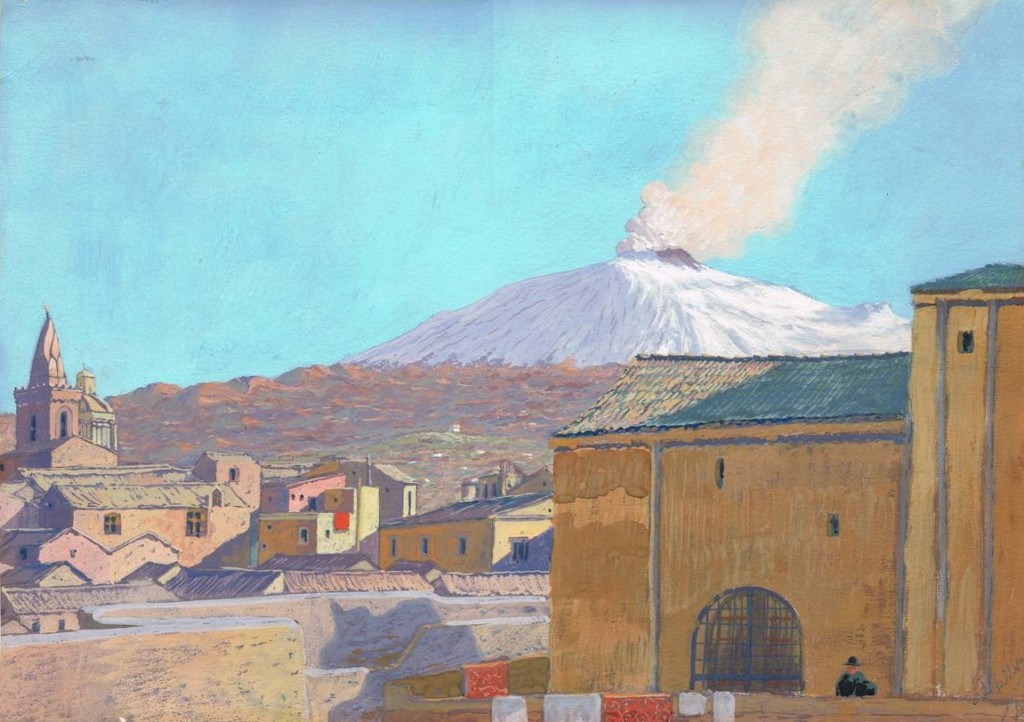

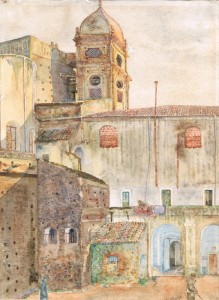

Major Kolbe was probably transferred from Cassino to Adernò (later renamed Adrano) in Sicily towards the end of 1917, as one of the paintings he brought back is marked “Christmas 1917”. It and a second one depict a courtyard surrounded by buildings, however, it is the painting with the view over Etna that helped me identify his place of internment as being the former monastery of Santa Lucia in Adernò.

Very little has been written about the Austro-Hungarian prisoners of war – where they were held and in what conditions – either by the nations that made up the Empire or by the countries in which they were interned. Despite being an integral part of the First World War the topic remained largely neglected for almost a century, the only information coming from the press and private sources, such as personal reminiscences and diaries. Then, in the run-up to the centenary of the conflict, it became the subject of several doctoral theses written by Italian students. It is mainly on their research that I have based the 2025 additions to the narrative of Josef Kolbe’s internment in Adernò.

Arrangements for the holding of Austro-Hungarian internees in the area of Catania were already underway by September 1915, when a representative of the Ministry of War requisitioned the former monastery of Santa Lucia for the holding of 700 prisoners, to be guarded by 200 Italian soldiers. Owing to the suppression of the monastic orders in 1866, the building was no longer a religious establishment, but its cells and outer walls lent themselves equally well to housing nuns as to holding prisoners. Despite its secular function, it was multilingual priests who were appointed to tend to the physical, psychological and spiritual needs of the internees, ensuring that they were treated humanely and that contact was made with their families. Furthermore, the predominantly Catholic prisoners were visited not only by the local bishop, but also twice, in 1916 and 1918, by the archbishop of Catania as an emissary of the Pope. On his second visit the archbishop brought medals bearing the images of the Sicilian saints Sant’Agata and Santa Lucia, which the men were delighted to hang around their necks as a memento.

right: Santa Lucia church door, 2008 |  |  |  left: Santa Lucia nave and altar, 2025 |

The former monastic compound takes up part of the north side of the via Roma, which since 2024 has been transformed from a busy thoroughfare into a pleasant pedestrian zone, bordered on the south by a large triangular park. To the north lie the narrow streets of the old town, giving way to the suburbs and gradually rising up the south-western slopes of Etna towards its smoking central crater. The 200 metre long imposing facade is divided into two parts by the church of Santa Lucia. The church doors appear to have remained locked since the monastery’s closure in 1902, but the scene of total neglect, revealed by a peep through the key-hole in 2008, has now been replaced by that of the richly restored baroque church. The east wing to the right of the church became a school in 1908, and today houses not only two schools but also, at the rear, a pensioners’ social club and a fire station. The west wing to the left of the church was given over to public use, later becoming the Austro-Hungarian prisoners’ place of internment, and is today occupied by an adult education institution on the top floor, the Adrano municipal offices on the middle floor and cafés, political parties and offices of various kinds on the ground floor. At the rear stands a post office, a driving school and the courtyard depicted in the paintings of 1917. The latter has remained largely unchanged since its use as the internees’ exercise yard, though today it is marked out as a sports ground and covered with netting.

Josef Kolbe left no description of his quarters at Adernò nor of how he occupied his time, but writing poetry was probably a major occupation as many of his poems, all dated February 1918, have survived. The following lines are drawn from an account written by a fellow officer, Franz Edouard Hrabe, who arrived at the monastery in February 1919, by which time Josef Kolbe had already been released. During Hrabe’s internment about sixty officers (“German”, Polish, Ruthenian and Hungarian) were held in the monastery, together with their servants, for whose services they paid. The first problem to be overcome was obtaining new clothes and shoes to be worn at mass and on the rare occasions when they were allowed outside the camp, though the main item of clothing worn during the heat of the summer was swimming trunks. According to Hrabe, the Sicilians had an aversion to water and washing, which they considered bad for one’s health: “far male”. This had perhaps more to do with the fact that mosquitoes were known to breed in water courses and ponds and were responsible for infecting humans with malaria (“bad air”). Josef Kolbe found this out to his cost, suffering from bouts of the disease for the rest of his life. The prejudice against water meant that there were no showers in the monastery before the prisoners took it upon themselves to build some. They were then requisitioned when it was deemed necessary that the Italian military should take a bath!

The officers were held on the middle floor, whereas the rank and file were assigned to the top floor, which was no doubt much hotter in summer, especially as the rear windows were bricked up. Some of the windows afforded a view over the via Roma, from which the internees could watch the comings and goings of the local populace. In the summer “il corso” took place on Sundays from midnight until 2 am, after which they were at last able to sleep until well into the morning, when the heat would drive them from their beds. Hrabe shared his cell with a fellow officer and also a crab, which lived in a water-filled bowl and was fed worms, and a gecko, which was allowed to roam the walls and ceiling and keep the fly population down. There was no shortage of food; bread with lettuce, sliced lemon, tomatoes or peppers became the favourite breakfast fare. Warm dishes of rice, macaroni and mutton appeared regularly on the varied menu, and all cooking was done with olive oil.

Hrabe seems to have developed a liking for Italy and Sicily and a genuine respect for the priests and nuns who showed him kindness and nursed him back to health. His description of the conditions he experienced at Adernò is in sharp contrast to that reported by the Neue Freie Presse in its article of 20 June 1918, where a captain of the Austro-Hungarian army who had returned from internment in Italy recounted the conditions experienced by the rank and file at the same camp. He related how in the summer of 1917 Austro-Hungarian soldiers were employed “to water citrus and orange groves in regions infested by malaria, which in the summer months were left unattended by the local population. As a result many fell ill and died of malaria, and in the camp at Adernò one could see emaciated men, reduced to skin and bones, who could barely put one foot in front of the other”. The rest of the article describes the sometimes appalling treatment suffered by the prisoners of war. As ever, the truth probably lies somewhere in between.

Adernò prison camp, past and present

|  |  |

|  |  |  |

In October 2025 I was accorded the privilege of a guided tour of the former monastery, which allowed me to see the parts of the west wing that were no doubt familiar to Major Josef Kolbe. My visit started at the rear of the building in the ground floor courtyard, the internees’ former exercise yard, and was followed by a tour of the now unoccupied nuns’ quarters on the middle floor. These are completely separate, now as they were then, from the rest of the middle floor, which housed the Austro-Hungarian officers, but is today occupied by the Adrano municipal authorities. Access was denied to upper floor where the rank and file prisoners were held, but this was compensated by a tour of the church where I witnessed at first hand the care that had been taken in restoring it. My visit was concluded in the office of the Adrano *Pro Loco where I received with great ceremony the society’s banner from the hands of its president, Cavaliere Nicolò Moschitta. My thanks go to the president for organising and guiding the visit and, together with the Pro Loco architect Nello Caruso, for directing me to several recent studies on the Austro-Hungarian prisoners’ internment in Sicily. Thanks are also due to my friend Angela Guadagnino, my interpreter during the interview with TVA Sicilia. Finally, I am indebted to the art historian Massimo Liccardo, without whose intervention on my behalf my eventful and enjoyable day in Adrano would not have been possible.

|  in former exercise yard, 2025 |  president of Adrana Pro Loco, 2025 |  from Cav. Moschitta, 2025 |

*Pro Loco societies are voluntary, non-profit organisations which promote local traditions, places of interest and produce, while enhancing the quality of life of the local populace.

Sources:

In Feindeshand: In der Gefangenschaft, 3. In Sizilien, F. Ed. Hrabe

Franz Edouard. Hrabe: https://www.kohoutikriz.org/autor.html?id=hrabe&t=p

Die Behandlung der Kriegsgefangenen in Italien, Neue Freie Presse, 20.06.1918, p. 27: https://alex.onb.ac.at/cgi-content/anno?aid=nfp&datum=19180620&seite=27&zoom=33

«Nessuno è rimasto ozioso»: campi di concentramento e prigionieri austro-ungarici in Italia durante la Grande Guerra (1915-1918), Dott.ssa Sonia Residori: https://iris.univr.it/bitstream/11562/957759/1/Tesi%20dottorato%20Residori%202017.pdf

L’Arcivescovo Francica Nava, Il Clero di Catania e la prima Guerra Mondiale, Dott.ssa Anna Gagliano: https://tesidottorato.depositolegale.it/handle/20.500.14242/77029

Pro Loco Adrano: https://www.prolocoapsadrano.it

Massimo Liccardo: https://independent.academia.edu/MassimoLiccardo

Dall’Inghilterra ad Adrano per ricostruire le vicende storiche del nonno: https://www.facebook.com/reel/1001570578782545