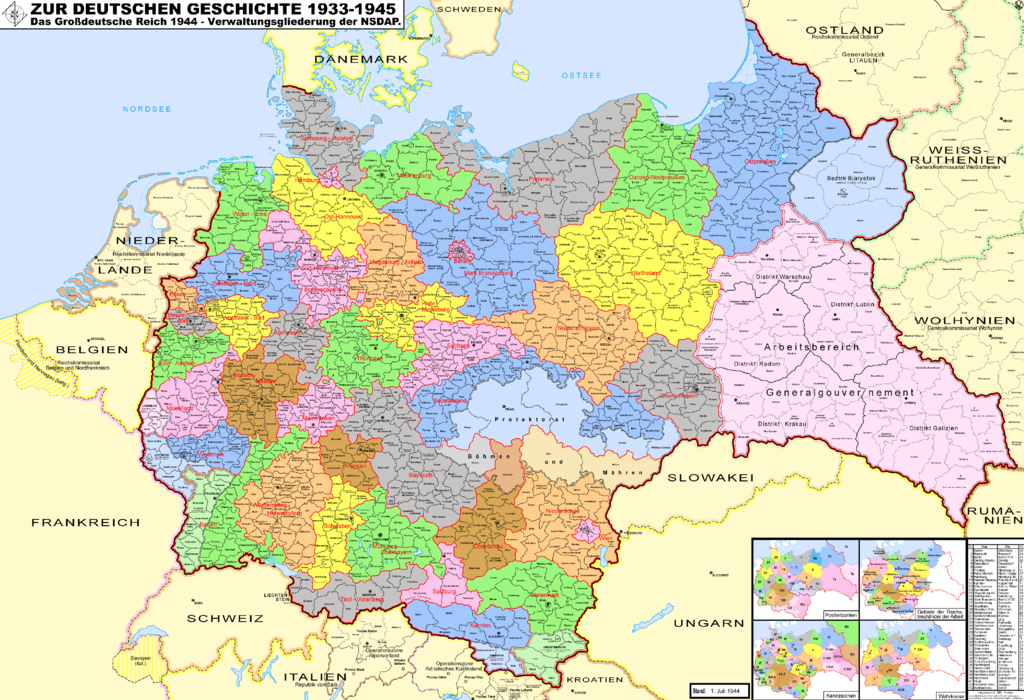

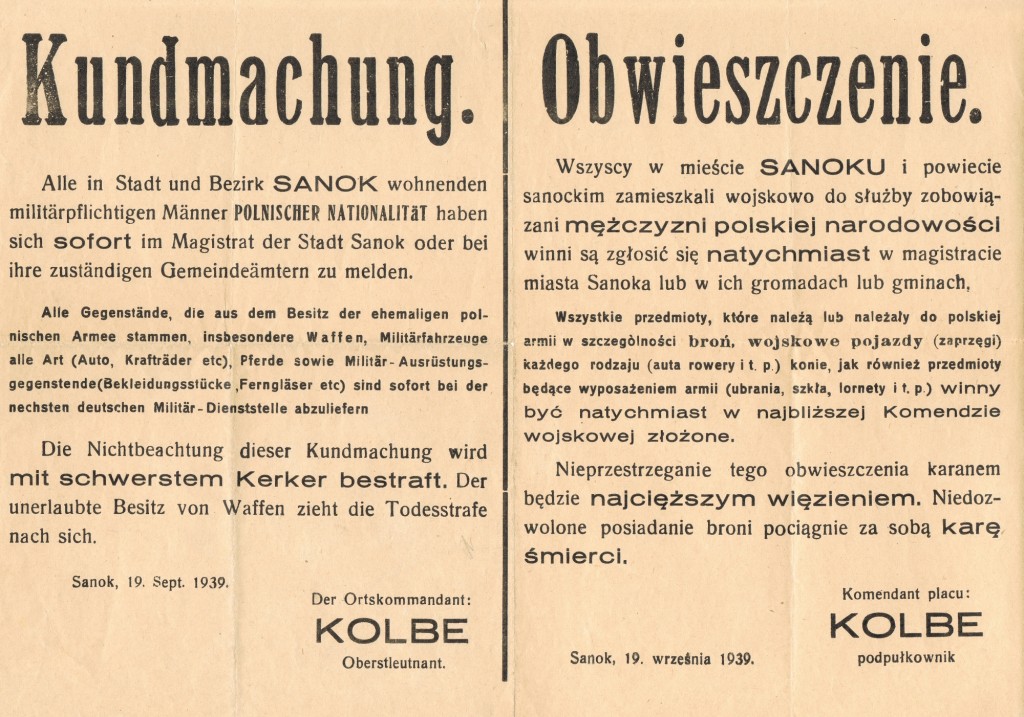

Lieutenant Colonel Josef Kolbe was called up on 26 August 1939 and within four hours he had taken command of the I/523 Kommandatur which was set up in Horn. He swore the obligatory oath to Hitler on the following day, and on 28 August he and his formation were already on their way by train to Mährisch-Ostrau (in the former Austrian Silesia, land of his birth) to join the 14th Army in the Poland Campaign. He was then transferred to Rosenberg (now Ružomberok) and Poprad in Slovakia, before being sent to Poland: Sanok in the middle of September and Miechow in early October.

By this time Josef Kolbe was already a sick man. He had known since the First World War and his imprisonment in Italy that his stomach was failing to function properly. None of the doctors he consulted was able to discover why he was not able to tolerate certain foods, so he devised a diet of his own, cutting out beer and fruit and allowing himself the luxury of half a glass of wine a day. In this way he was able to carry on doing sport (gymnastics, ski-ing, etc.) or studying for 10 to 15 hours a day. However, the control he had managed to maintain for so many years was unsustainable in wartime conditions and towards the end of October 1939 the stomach problem recurred. On 2 November he was admitted to the field hospital of the I/521 Kommandatur in Krakow, with his weight down from 64 kg. to only 47 kg. His condition was considered sufficiently serious to warrant giving up his command temporarily and returning to Vienna for wide-ranging tests. On arrival on 12 December he was put in the capable hands of Professor Dr. Hans Finsterer, a highly regarded surgeon specialising in stomach operations who, after imposing six days’ artificial nutrition, cut out more than two-thirds of Josef Kolbe’s stomach under local anaesthetic in a three hour operation. The verdict was not encouraging: advanced stomach cancer.

As usual, Lieutenant Kolbe was eager to get back to the front to serve the fatherland, but he knew that building his strength again would be a long and difficult process, requiring the utmost patience. It would be six months before he was allowed to take up his command again, but he must have suffered a relapse shortly afterwards, as his army record shows that he was demobilised on 20 July 1940, thus ending his wartime service.

The war only served to exacerbate the circumstances of the civilian population. Within a few weeks of his mobilisation, Josef Kolbe had given up his accommodation in Mödring and moved officially to Vienna, probably with the intention of saving on rent for the duration of the war. His new address was 109 Gumpendorferstrasse, flight 1, floor 3, flat 18, which appears to have been the flat hitherto occupied by Ilse and Gerda. He had also given up all pretence of belonging to a religion, by officially leaving the Lutheran faith, which he had adopted in order marry his Transylvanian Saxon wife. It was also a money-saving measure, as those belonging to a church were liable for church tax. Despite these steps, the financial situation of the Kolbe family remained critical, as witnessed by the letter Josef Kolbe dictated from his sickbed in January 1940 to the pension office, requesting an increase in housing benefit backdated to 1 October 1939. The reasons for his claim were that rents were higher in Vienna than in Mödring, Kurt had been mobilised and was no longer receiving his civil servant’s salary, Gerda was jobless but was needed to keep house, Ilse was earning a mere 110 Reichsmark a month from her job with the AEG-Union and that he had to help out with his meagre Lieutenant Colonel’s allowance.

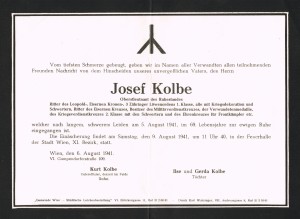

It is not known whether his request was granted, as no further documentation is available before the publication of Lieutenant Colonel Josef Kolbe’s death on 5 August 1941. His stomach cancer, which had been eating away at his health for so many years, finally carried him off. It was not a death that this proud and uncompromising soldier would have wished for himself. One wonders what orders he, as a senior officer of the Wehrmacht, would have been required to carry out and whether he would have adhered to his principles to the end. I am inclined to believe he would not have hesitated to make a stand. He would have been proud of Kurt’s war record in Greece and on the Russian front and the timber exporting business he later set up. Gerda’s later job in a large insurance company in Vienna would also have met with his approval. But would he have given his blessing to Ilse, who worked for the British occupation forces in post-war Vienna and who went on to marry one of their number, Corporal John Leslie Pickering? We shall never know, though I suspect he might have mellowed with age.

Vienna, 2006 |  5 August 1941 |  Mödring churchyard, 2010 |  |

Josef Kolbe was in some respects a visionary but at the same time a man of his time and a product of his upbringing. Having delved into his life and presented as fair a portrait as a granddaughter is capable of, I believe that he could be content in the knowledge that he had lived a full and interesting life and had, above all, stood by his principles and done his duty as an officer of the German nation.

Sources:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hitler_oath

http://www.lexikon-der-wehrmacht.de/Gliederungen/Kommandantur/GliederungOK.htm

http://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hans_Finsterer