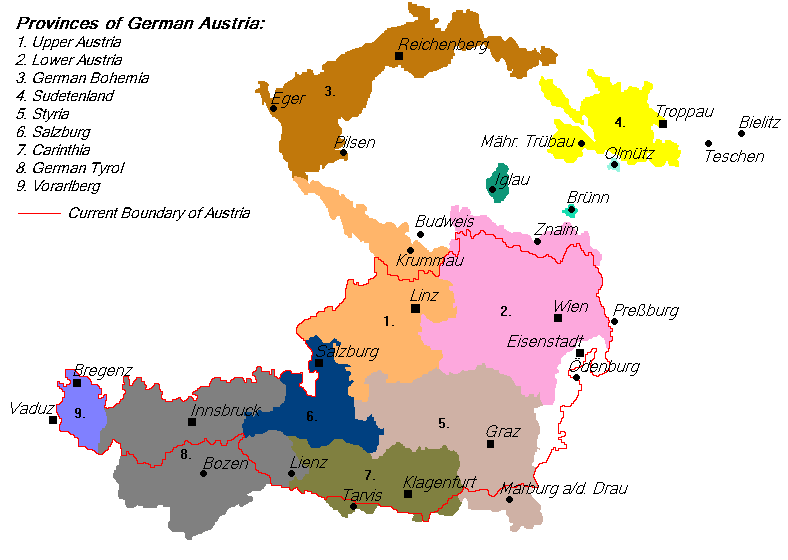

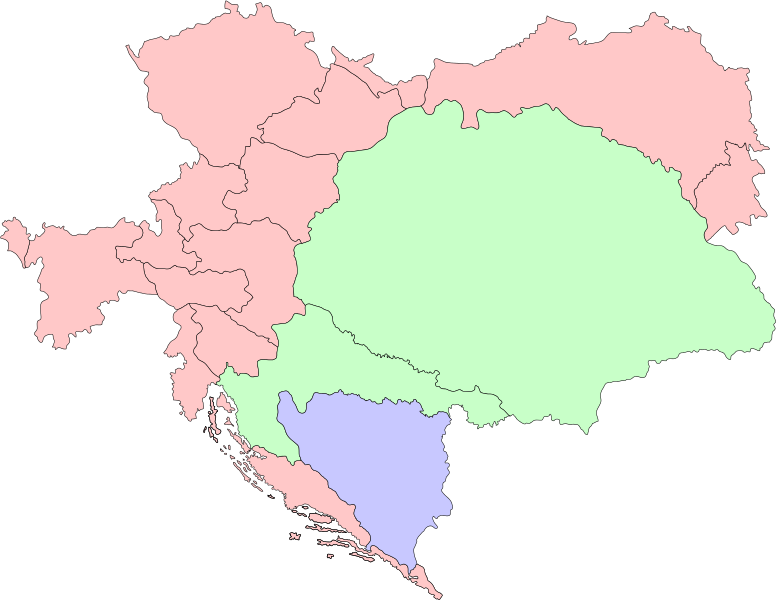

With the entry of the United States of America in the war, by January 1918 the Central Powers were heading towards inevitable defeat. It was at this point that U.S. President Woodrow Wilson set out his Fourteen Points, stipulating that the peoples of Austria-Hungary be accorded the “freest opportunity to autonomous development”. In response, Emperor Karl agreed to reconvene parliament and allow for the creation of a confederation, with each national group exercising self-governance. However, the nations saw in this an opportunity for full autonomy and were now bent on independence from Vienna at the earliest possible moment. In October 1918 Karl issued a proclamation with a view to setting up an independent Polish state made up of the ethnic Polish territories still in the hands of Austria, Germany and Russia. The rest of the Austrian lands were to be transformed into a federal union composed of four parts: German, Czech, South Slav and Ukrainian, each governed by a federal council, with Trieste having special status. But this was unacceptable both to the Allies and to the nations concerned, which one by one proclaimed their independence. Finally Hungary officially ended the union between the two countries, with the result that the Danubian and Alpine provinces of the Austrian heartland were all that remained of Karl’s realm.

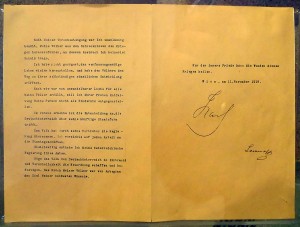

In the face of the forces ranged against him, Emperor Karl had no choice but to stand down. On 11 November 1918, on the same day as the armistice ending the First World War, he issued a carefully worded proclamation in which he recognised the German Austrian people’s right to determine what form their state should take, relinquishing his participation in the administration of it. He also released his officials from their oath of loyalty to him. On 13 November, he issued a similar proclamation for Hungary. Although these proclamations have been widely cited as abdications, no mention was made of the word in either document. Indeed, Karl deliberately avoided using it in the hope that the people of either Austria or Hungary would vote to recall him.

While these events were unfolding, Major Josef Kolbe had not remained idle. Having been released from captivity in Italy in June 1918, he was immediately sent to Belgrade, from where he requested eight weeks’ leave, after which he wished to be considered for a “difficult and spirited” command on the front line, calling for “insight, self-reliance, organisational skills, quick decision-making, energy and courage”! His request for a command was not granted, he was officially deemed unfit for service, but his request for leave was. His justification for a period of eight weeks was not only his wish to see his family again, but also his intention to travel to Transylvania to fetch his wife’s furniture and belongings from Fogarasch and sort out his affairs with his brother-in-law in Kronstadt. From there he planned to travel to Istanbul to take care of family matters with his friend and children’s guardian, Prof. Dr. Carl Jung, returning via Berlin and Hamburg in order to settle business matters there. It seems strange that someone who had recently been released from imprisonment on grounds of invalidity should wish to undertake such an arduous journey. The wounds that he had sustained on the Isonzo were probably healed by then, but Josef Kolbe was a sick man, having contracted malaria in Italy and suffering from an as yet undiagnosed stomach complaint. But his drive and energy overrode any health considerations, and I suspect that his trip was a cover for an attempt to rally support among his family, friends and acquaintances for retaining the Empire with Karl at its head and Transylvania an integral part of it.

Romania had entered the war on the allied side in the hope of gaining the Romanian-speaking territories of Transylvania, Bessarabia and Bukovina in the event of an allied victory. By mid 1918 Josef Kolbe must have been aware that the fate of his “second home” hung in the balance and he was determined to defend the status quo. He was able to rally his sister-in-law Luise to the cause and probably his brother-in-law Adolf too, both of whom were still living in Transylvania. Unfortunately it is not known how he intended to implement his plan, but it obviously failed, as Josef Kolbe ended up being declared persona non grata in what had by then become Romania and Luise, now as a Romanian citizen, served a prison sentence for her part in the venture. Little did Josef Kolbe know that his eldest daughter Ilse would later marry a compatriot of the former Princess of Edinburgh, who as the charismatic Queen Marie of Romania was to charm and bully the allied leaders at the Paris Peace Conference into granting the three coveted territories to Romania, consolidating Austria’s loss of Transylvania. Furthermore, John Leslie Pickering, the son-in-law he did not live to meet, was the nephew of a governess to the children of King Ferdinand and Queen Marie!

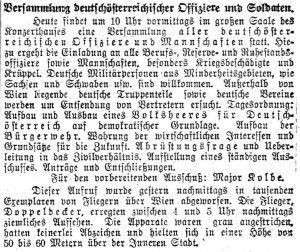

Fremden-Blatt, 03.11.1918

The Republic of German Austria had also been proclaimed in November 1918, with its provisional constitution declaring it a democracy and part of the German Republic. Whereas Romania had gained 60%, Austria was to lose 60% of its territory and felt it needed to unite with Germany to remain viable. Major Kolbe’s vision of the greater German nation meant that he was a staunch supporter of unification and on 3 November he called a meeting in the Vienna concert hall for all officers and soldiers, ostensibly to discuss how best to defend the integrity and interests of the new German Austrian republic. Unmarked planes dropped flyers advertising the event over the streets of Vienna, to the consternation of many who took them to be enemy planes. Though this novel marketing feat ensured massive attendance, the event proved unsuccessful, as the pro-German speakers’ proposals were all rejected. Josef Kolbe’s suggestion to call on the German army to maintain order if necessary was particularly badly received, the loud boos drowning his speech so that he had to leave the platform. Not only was his audience opposed to any rapprochement with Germany, but so were the allies, and German Austria’s later claim to all the ethnic German areas of Cisleithania proved a step too far. In October 1919 the new country was obliged to ratify the Treaty of Saint Germain-en-Laye, by which it was renamed the Republic of Austria and its independence rendered inalienable, effectively barring any attempt at unification with Germany and restricting its frontiers to roughly those of today.

|  |  |

This, however, did nothing to discourage Karl and his supporters from plotting to reinstate him as Emperor. The attempts of March and October 1921 to retake the throne of Hungary are well documented. One of the leaders was Anton Lehár, who was nominated Minister of Defence of the future government. He was the brother of the composer Franz Lehár, Josef Kolbe’s friend. Colonel Anton Lehár and Lieutenant Colonel Josef Kolbe must have become acquainted while they were both serving with the 50th Infantry Regiment in the 1890s, and despite the lack of documentary evidence, I think it is safe to assume that the Lehár brothers encouraged Josef Kolbe to join the Austrian attempt to restore Emperor Karl. He freely admitted to having taken part in the plot under the leadership of General August von Cramon, who served as Prussia’s military liaison at the k.u.k. headquarters in Vienna from 1915 to 1918.

Josef Kolbe was also to be disappointed in this venture. Nevertheless, he remained a true monarchist and attributed any failings on the part of the Emperor to his advisers, whom he regarded as unprincipled men acting wholly out of self-interest. He could not envisage a future without a monarch, the guarantor of morality and order, treating the peoples of his disparate realm equally, and he was dismissive of anyone who considered the restoration of Karl to the throne as a danger.

Sources:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charles_I_of_Austria

http://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Karl_I._(Österreich-Ungarn)

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Marie_of_Romania

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/German_Austria

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charles_IV_of_Hungary’s_conflict_with_Miklós_Horthy

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Anton_Lehár

AustriaN Newspapers Online: http://anno.onb.ac.at