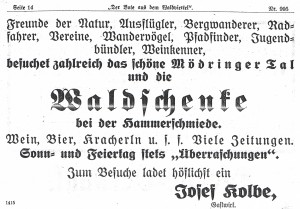

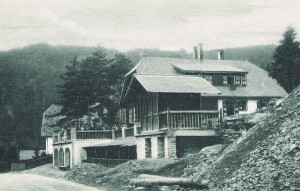

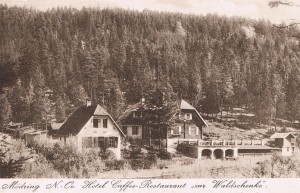

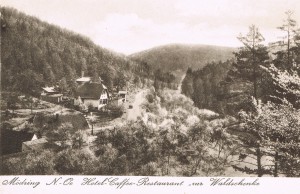

It seems to have been Emilie’s brother, Adolf Däubel, who encouraged Josef Kolbe to try his hand at the hotel business. The idea was to create a haven of peace in the heart of the countryside where the inhabitants of Vienna could get away from the city and enjoy all that nature has to offer. By 1913, having left Hamburg, Josef Kolbe was scouting the area around Horn, Lower Austria, where he had spent four happy years at school, for a house for his family and a suitable building to accommodate his dream of a nature retreat. These he found in a hamlet known as Waldschenke on the Horn road that runs through the woods 5 kms north of Horn and 2 kms north of the village of Mödring, the seat of its local authority. The hamlet consisted of four buildings: a hammersmith’s workshop, situated on the south side of the road near the brook, the recently built smith’s house next door and, diagonally opposite on the north side of the road, the Waldschenke itself, meaning the “inn in the woods”, beside the innkeeper’s house. It was the latter two that Josef Kolbe bought to realise his business project and to accommodate his family. He intended to transform the run-down Waldschenke, described in the press as a blockhouse, into a rustic but comfortable hotel, café, restaurant and, above all, summer and winter nature retreat.

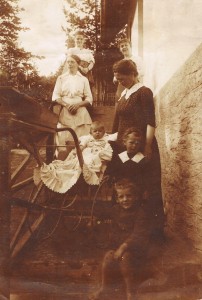

Ilse Kolbe and Gerhard Kreuz,

last day in Fogarasch, 20.06.1915

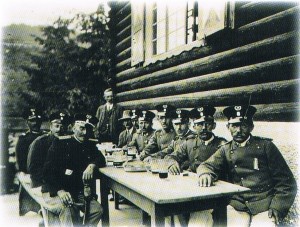

Josef Kolbe no doubt threw himself into his latest project with his usual enthusiasm, and by 1914 the new Waldschenke was taking shape. But his ambitions had to be put on hold when he was called up on 1 August to return to his former regiment, with whom he would serve throughout the First World War. Emilie and Ilse seem to have divided the rest of 1914 and the first half of 1915 between Lower Austria and Transylvania. However, when in 1915 it became clear that Romania was negotiating to enter the war on the allied side, Josef Kolbe had them leave Transylvania for the last time and travel back to the Austrian heartland. The family had some brief reunions in Kassa (now Košice in Slovakia), where Captain Kolbe was serving behind the Galician front. Their second child, a son called Kurt, was born in Horn in February 1916. After the birth, the mother and two children took up permanent residence in the Waldschenke family house.

It is not known where Captain Josef Kolbe met Professor Dr. Carl Jung, a German dental surgeon, but the two men must have become good friends, as Carl Jung accepted to be the godfather of baby Kurt, attending his christening in Horn in March 1916. Furthermore he agreed to become the guardian of both Ilse and Kurt in the event of Josef Kolbe’s death. Professor Dr. Carl Jung served with the German Military Mission in Constantinople during the later war years.

The war was to drag on another two years. Despite the presence of servants, Emilie must have felt extremely isolated in her house in the middle of the woods and probably very homesick. One night she was woken by a would-be intruder and did not hesitate to reach for one of her husband’s guns and fire it out of the window. This put an end to uninvited guests! Her isolation was relieved for a while in the summer of 1916, when she received a visit from her sister Julie, now Frau Kreuz, and her son Gerhard. Ilse and Gerhard were very close, having spent long months together at the Däubel family house in Fogarasch. The Kolbe family had to wait another 15 months before being reunited. Major Kolbe was released from captivity in Italy in June 1918 but was immediately sent to Belgrade. Once there he felt justified in applying for eight weeks’ leave, not only to see his family again, but also to settle a number of family and business matters in various parts of Europe, after which he considered he would be fit enough to be given a new command. His request for leave was granted, but his request for a command was not, as he had been released from imprisonment on grounds of invalidity, so once his leave was over and with the end of the war looming, he returned to his family at the Waldschenke and set about completing his nature retreat.

The Waldschenke was opened with great pomp on 1 May 1919. The half timbers on the lower outside walls of the Swiss style chalet and the boarding on the upper outside walls had been repainted dark brown. New green and white shutters embellished the renovated windows. No doubt renovation work was also carried out inside. A wide terrace was built in front of the house, facing the road and the brook beyond, with a narrower part stretching to the right of the house, covering the bowling alley below. Tables, chairs and benches covered the whole area in the summer and were stored in the little hut at the end of the terrace in the winter. The café and restaurant served delicious food and local wines to trippers and passers-by, and rooms were available with full board (four meals a day!) for longer stays. Emphasis was placed on the comfortable rusticity of the Waldschenke, where guests were invited to relax over a glass of wine or beer and a large variety of newspapers of all political persuasions, and the natural beauty of its surroundings, which offered numerous opportunities for hiking, cycling, hunting, fishing and bathing. Josef Kolbe’s ambitions, however, did not stop there: he apparently envisaged building a cable car to convey his guests up the slopes.

|  Der Bote aus dem Waldviertel |  |  |

The third Kolbe child, a daughter Gerda, was born in Vienna in May 1920. By this time it can be assumed that the Waldschenke had not been performing as well as Josef Kolbe had hoped. As early as 1919 he was sending increasingly desperate letters to the War Ministry to be considered for a higher pension in the light of his rank and his war record. In the meantime his elderly mother had moved in with the family. Sometime after the death of Josef Kolbe’s father in Znaim in 1894, she had moved to Retz, just south of the border with the new state of Czechoslovakia, to be close to her sister and other members of the Gödel family, but by the 1920s she was in her late 70s and probably too frail to look after herself. Josef Kolbe was finally promoted to the rank of Lieutenant Colonel sometime between 1921 and 1924. His pension was presumably increased accordingly, however, it remained insufficient to support his enlarged family, pay his debts and keep his ailing business running.

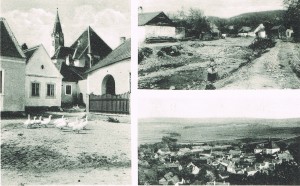

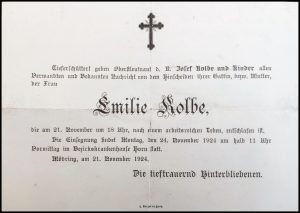

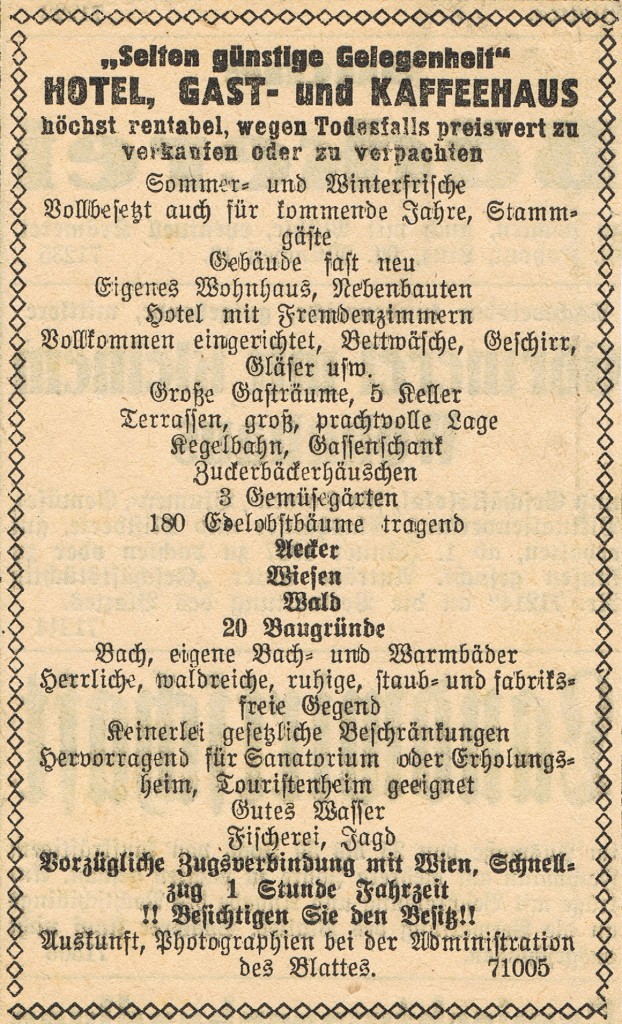

Emilie, who was already 43 years old when she gave birth to Gerda, never fully recovered from the difficult pregnancy. Her health deteriorated over the following four years, during which time a great deal of money was spent on medical bills, but to no avail, and she died in November 1924 following a stroke. Josef Kolbe finally had to admit that his business venture had failed and it was probably with deep regret that he put the Waldschenke up for sale in 1925. Ilse, being the eldest child, was taken out of school to keep house and look after her grandmother. She was later sent to Vienna to work in a tavern, with strict instructions to send her wages home. She regretted leaving school without any qualifications for the rest of her life, and her brother and sister missed her terribly, as she had become a second mother to them. By 1928 the Waldschenke and the family house had finally been sold, and Josef Kolbe had moved into the village of Mödring, renting a house from the Kohl family in the centre of the village by the same brook that ran beside his unsuccessful nature retreat.

The Waldschenke continued to operate until at least 1935. A combination of the Great Depression and the Second World War probably sounded the death knell on the enterprise.

|  |  |  |

|  |  |  Herta Schudermayer, Hazel Pickering |

Times were hard in the run-up to the Second World War. Colonel Josef Kolbe found himself in the same situation as his late wife during the previous war: alone in the house with small children. His mother cannot have been of much help because she was by then old, though this tiny woman must have had a strong constitution, as she was to die in 1937 at the age 93! And his attempt to provide a mother for his children by proposing marriage to Emilie’s still single younger sister Luise was rejected. This was hardly surprising because, apart from having first-hand experience of his restless and overbearing character, she had been encouraged by him to get involved in the abortive attempt to bring back Emperor Karl from exile and restore him to the throne, for which she had spent time in prison (see Aftermath)! So Josef Kolbe had to face up to the day-to-day reality of – in his own words – cooking, washing, ironing and sewing. At one point he turned up on Emilie’s cousin’s doorstep in Mödling with Kurt and Gerda in tow, leaving the children with her with orders to look after them. Elisabeth Langer had also married a soldier from Austrian Silesia, Adolf Englisch, who had also been stationed in Transylvania. She was now a widow herself with three small children. The children delighted in each other’s company, Gerda and Freya Englisch, who were the same age, remaining close friends for the rest of their lives. It is not known if the question of money, or indeed marriage, was raised, but Elisabeth was less than delighted by the peremptory manner in which she had been put upon, and looking after five children proved too much, so Kurt and Gerda soon found themselves back with their father.

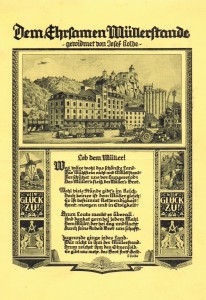

poetry and prose

in praise of the miller, 1936

Josef Kolbe occupied his mind as best he could, organising events both in Horn and Vienna, composing music and writing books and poetry. In 1933 his book in celebration of the 275th anniversary of the founding of his old school was published. At the same time he was writing poetry of heartfelt tenderness, a side of him that very few people, if any, had ever witnessed. He also took an interest in the broad spectrum of politics, but not party politics. His hostility was directed in particular at the Vaterländische Front, which was set up in 1933 along the lines of the Italian Fascist Party, advocating Austrian nationalism independent of Germany, on the basis of protecting Austria’s Catholic identity from what was considered Protestant dominated Germany. A number of incentives were offered him to join the party, which he consistently refused, as its politics did not sit well with his wider concept of Germanness and ran counter to his honour as an officer. He claimed that it would have been easy to set aside his principles and in this way gain promotion to the rank of Lieutenant General or General, like many of his fellow officers had done, especially as the leader of the Vaterländische Front had been appointed Chancellor of Austria by President Wilhelm Miklas, a former director of Josef Kolbe’s old school and still a resident of Horn. He was no friend of the Communist Party or the Social Democratic Party either. The feeling was mutual with the Social Democrats, as he was known to have been active in the attempt to restore the Habsburg monarchy (see Aftermath). Despite having claimed not to be interested in party politics, Josef Kolbe became a member of the National Socialists in 1931, probably because the ideal of the greater German nation propagated by them was closest to his way of thinking, and he most likely approved of the annexation of Austria and the take-over of the Sudetenland (of which the land of his birth Austrian Silesia was a part). However, as a man of principle, it is unlikely that Lieutenant Colonel Josef Kolbe approved of Hitler’s more extreme ambitions and the ruthlessness with which he intended to achieve them.

In the meantime Ilse had left the tavern where she had become a skilled cook and was working in a kindergarten in Baden, while trying to make up for her lack of formal education by learning typing and English. Later she practised her English while living with a family near Beaconsfield, Buckinghamshire, as perhaps one of the first au pairs in England. This was shortly before the outbreak of the Second World War and she found herself in a difficult position, being accused of spying by the British and also by the Austrians on her return home! In those times of depression Ilse’s typing and language skills helped her secure a greatly sought after job with the AEG-Union in Vienna. Kurt was by then a civil servant and Gerda, having completed her secondary schooling, was doing compulsory labour service as a lady’s help in Professor Dr. Carl Jung’s household in Berlin when war broke out.

|  |  |  |

Sources:

Der Bote aus dem Waldviertel, newspaper articles provided by Dr. Erich Rabl, former teacher at the Horner Gymnasium and local historian

Chronik der Häuser von Mödring im Jahre 2005, Herta Schmudermayer

Mödring – Geschichte, Geschichten & Gedichte, Herta Schmudermayer

AustriaN Newspapers Online: http://anno.onb.ac.at

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fatherland’s_Front

http://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vaterländische_Front