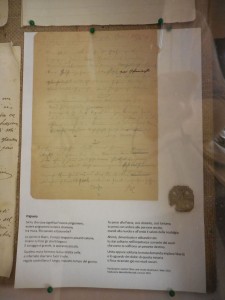

Major Kolbe was held at the Certosa di Pisa, a Carthusian charterhouse situated at the foot of the hills overlooking Calci, in March and April of 1918. The length of his stay and his sentiments as a POW come from his book of poems, the only documentary evidence he left of his internment at Calci.

The Certosa di Pisa at Calci was founded in 1366 by the then archbishop of Pisa in fulfillment of the last will and testament of Pietro di Mirante della Vergine, a Pisan merchant. Thanks to donations from rich Pisan families, it was gradually enlarged to include a refectory, a chapterhouse and the monks’ cells, but it owes its present appearance to the work carried out during the 17th and 18th centuries. With the suppression of the religious orders during the Napoleonic and Savoy periods in the 19th century, the Carthusian community was dissolved and, by the time the monks returned, the Certosa had become the property of the state, who obliged them to open part of it to the public. The Carthusian monks finally left the Certosa in 1969 and it became a museum in 1972. The high points for today’s visitor are the large collection of valuable works of art, the pharmacy dating from 1643, and the Natural History Museum dating back to the 16th century.

|  |  |  |  |

The Certosa played an important role during the First World War. From January to March 1915 it was the barracks of the 32nd Artillery Regiment of the Italian army, before becoming a hospital for Italian soldiers from October 1915 to December 1916. Between January 1917 and December 1919 it was transformed into a transit hospital for Austro-Hungarian POWs, undergoing examination and often months long observation to distinguish the bona fide from the self-inflicted wounded and sick, with a view to their exchange for Italian counterparts. Alongside this, in 1918 the Certosa took in a number of Italian refugees from those parts of the country that had come under enemy occupation. It was only in 1920 that it was finally restored to its original function.

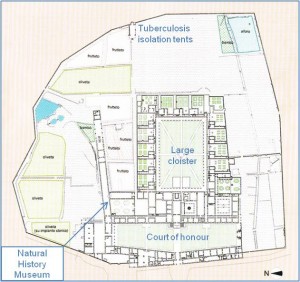

Numerous alterations were necessary to transform the Certosa into initially barracks, then a military hospital and later a secure hospital for enemy POWs. The latter involved the construction of a sentry box at the entrance and the erection of walls and bars to prevent the prisoners from escaping and entering certain areas of artistic or historical importance. The Austro-Hungarian officers were accommodated in rooms in various parts of the complex, but the rank and file prisoners most probably occupied and received medical treatment in the buildings of the former granary, storerooms and stables which stretch over 4,000 square metres into the orchards to the left of the the monastery, previously home to the troops of the 32nd Artillery Regiment of the Italian army. (In 1986 the buildings became the Natural History Museum, originally located at the University of Pisa since its founding in the 1500s by Ferdinando I dei Medici, and boasts a wonderful collection of meteorites, minerals, fossils, mammals, fish, reptiles and birds, not forgetting the enormous whale skeletons in the hall of the whales). Those prisoners suffering from infectious diseases, who originally occupied a number of isolation rooms within the monastery, were moved in 1918 into tents in the grounds against the back wall of the complex, well away from the main buildings, probably in response to local pressure.

The enforced presence of enemy POWs at the Certosa did not meet with the approval of the Superintendent of the Pisa Monuments, Peleo Bacci, who was not only obliged to suspend all cultural visits but was also concerned about the effect its function as a prison would have on the historical buildings. However, his numerous letters of complaint to the authorities fell on deaf ears. Nor did the local populace appreciate having enemy soldiers in its midst. Not only were they responsible for the death of their compatriots, but the cost of their upkeep was also becoming increasingly expensive with the arrival of more and more sick and wounded prisoners. However, the townsfolk of Calci feared in particular for their health, especially when in mid 1918 the Certosa was required to accept prisoners suffering from infectious diseases, mainly tuberculosis and but also tetanus, septicaemia, gangrene and typhus. Letters of protest about a potential epidemic were once again written by the hospital management, the municipal authorities and the local MP and articles appeared in the press, but to no avail.

As the Certosa gradually became established as a transit hospital, prisoners began to be sent from POW camps in other parts of Italy, resulting in a total number of 376 (including 48 officers) on 23 June 1917. By 1 August 1917 the tally stood at 430. At the beginning of 1918 the sick and wounded were arriving directly from the war zones and in March 1918 their number peaked at 658, obliging the hospital management to refuse entry to any more.

With the arrival of increasing numbers of prisoners, the cost of transporting and feeding them and running and maintaining the Certosa as a hospital rose rapidly. This, coupled with the economic situation brought on by the war, meant that food rations had to be reduced in March 1918. It was therefore decided to put the skills of the men to good use. Some were employed as bricklayers and labourers, others worked in the sick bays, the kitchens and the laundries. There was even a shoemaker and a tailor, and those of peasant stock had the privilege of creating a kitchen garden to grow potatoes and beans in parts of the court of honour and the large cloister.

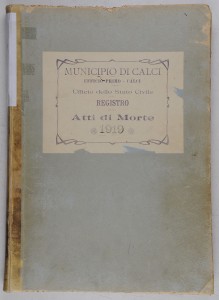

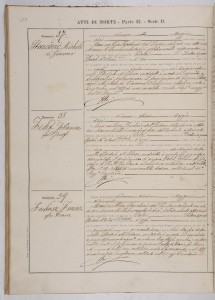

Deaths inevitably occurred among the prisoners. Over the three years that the Certosa was used as a hospital for Austro-Hungarian POWs there was a total of 188 deaths: 30 in 1917, 70 in 1918 and 88 in 1919. Only 10% of the deaths were attributable to wounds sustained at the front or amputations. The rest were the result of infectious diseases – tuberculosis, malaria, respiratory complaints, enteritis and typhus – and even when the final cause of death was noted as infarction, cerebral hematoma or pulmonary oedma these usually constituted the final manifestation of an infectious disease. The deaths were recorded meticulously with the deceased’s name; father’s name; age or date of birth; date of death; place of birth; nationality; rank and regimental number; marital status, profession and religion; and cause of death. All nations of the Austro-Hungarian Empire were represented among the dead, with a majority of Austrians and Hungarians, their religion being mostly Catholic, though there was a small number of non-Catholics and Jews. All were buried in Calci cemetery according to their religious rites, first in individual graves but, when the numbers increased and space became scarce, it was decided to transfer the remains to an ossuary which is still standing today.

|  50th Infantry Regiment |  Calci cemetery, 2015 |  Calci cemetery, 2015 |

It was finally decided that Major Kolbe met the prisoner exchange criteria as set out in an agreement between the Italian and Austro-Hungarian governments. He qualified for the category “grands blessés et grands malades”, possibly as a result of the wounds he sustained on the Isonzo or the malaria he contracted at Adernò or both. Those prisoners who were fit to travel were transferred to the Ospedale Abbondio at Como, the last port of call for the Calci POWs before being released. (Those suffering from tuberculosis were sent to the Ospedale Coronata at Genova.) It is possible that Josef Kolbe was one of a batch of 200 POWs transferred to Como at the beginning of April 1918, as he was exchanged for an Italian prisoner on 15 June 1918. To his great astonishment he realised that they were acquainted. The Italian had been a diplomat attached to his country’s consulate in Hamburg at the same time as the retired Captain Kolbe had been a factory manager in the suburb of Pinneberg, and the two men had no doubt met socially.

In writing this piece I have leaned heavily on the extremely thorough research carried out by the team from the University of Pisa, headed by Antonella Gioli, whose findings formed the basis of the exhibition entitled ‘Solitudo’ Violata: La Certosa di Calci nella Grande Guerra, which was held at the Certosa from 27 June to 4 October 2015, and the accompanying book, La Certosa di Calci nella Grande Guerra. I am truly grateful to Antonella Gioli and Anna Salvadorini for taking the time to give me a guided tour of the exhibition and those parts of the Certosa not normally open to visitors.

Sources:

Museum of Natural History: http://www.msn.unipi.it

Pisa Archives: http://www.aspisa.beniculturali.it

Archives of the History of the Army: http://www.esercito.difesa.it/storia/grande-guerra

La Certosa Monumentale di Calci: http://artesalva.isti.cnr.it/en/charterhouse-calci

Exhibition ‘Solitudo’ Violata: La Certosa di Calci nella Grande Guerra: http://lavitadelleopere.com/la-certosa-di-calci-nella-grande-guerra

La Certosa di Calci nella Grande Guerra, edited by Antonella Gioli

La Prigionia di Guerra in Italia 1915-1919, Alessandro Tortato

In Feindeshand: Invalidenaustausch und Heimkehr, Major Adalbert Haid-Haidenburg

E mentre Berta filava, Bruna Lupetti Battaglini

Dove nascono i Quadrifogli, Bruna Lupetti Battaglini